The IMF has ranked Australia’s housing market as being the second most high-risk country of 27 countries, which CoreLogic attributes to five reasons.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which works to achieve sustainable growth and prosperity in financial markets across the 190 member countries, has suggested that Australia is second only to Canada when it comes to being at “housing market risk”.

In its World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery report, released this week (alongside its Global Financial Stability Report), the IMF outlined that economies with high levels of household debt and a large share of debt issued at floating rates are more exposed to higher mortgage payments, with a greater risk of experiencing a wave of defaults.

It flagged that while house prices rose to record levels in many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic — especially among advanced economies as a result of record-low interest rates, limited supply and “ample policy support” — it noted that house prices are now coming off the boil.

It flagged that, in the second quarter of 2022, quarterly real house prices fell, with about two-thirds of economies experiencing negative growth and the remainder positive but slower growth.

“Among advanced economies, the deterioration in the housing market was more pronounced in those that showed signs of overvaluation before and during the pandemic.

“With central banks hiking interest rates, mortgage rates climbed to an average of 6.8 percent in advanced economies in late 2022, up from 2.8 percent in January 2022. If mortgage rates continue to rise, demand for borrowing and house prices are likely to weaken further,” the report reads.

The authors continued that housing markets and prices are likely to cool more and be more sensitive to policy rate hikes in economies in which house prices rose more during the pandemic.

“In most cases, it is unlikely that an ongoing fall in house prices will lead to a financial crisis, but a sharp drop in house prices could adversely affect the economic outlook,” the IMF warned, stating that the build-up of “medium-term vulnerabilities warrants close monitoring and, potentially, policy intervention”.

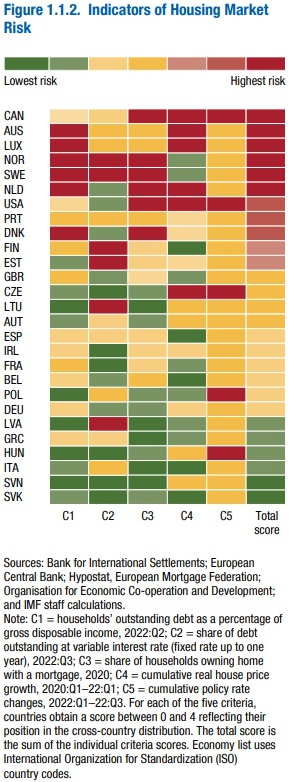

In a chart, the IMF said Australia was at highest risk for household debt levels (as a share of gross disposable income) and cumulative real house price growth — making it the second highest-risk housing market out of 27 countries:

Source: Word Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery; full report; April 2023, IMF

Five reasons for IMF’s conclusion, says CoreLogic

Reacting to the analysis, Eliza Owen, head of research at property data and analytics company CoreLogic Australia, suggested that there were five factors that would have fed into the IMF’s ratings.

These are:

- The fact that RBA figures suggested Australian housing debt represented around 145.4 per cent of the country’s total disposable household income (around $2 trillion) in June 2022 and is “still hovering around record highs”;

- Australia’s high portion of outstanding housing debt on variable rate terms (around 70 per cent at the close of 2022), meaning Australian mortgagors feel rate pain more quickly than those in the US and Europe;

- The country’s high proportion of home owners with a mortgage (which the 2021 Census found was 35 per cent);

- The fact Australians are experiencing their sharpest rate-hiking cycle on record, as the underlying cash rate went from emergency lows of 0.1 per cent to 3.6 per cent in less than a year — and the impacts are still coming through the system; and

- Australian home values rose 25.4 per cent (or 19 per cent when accounting for inflation), between March 2020 and March 2022.

Noting the above, Ms Owen said, “Entrants to the housing market have taken on more debt to buy homes over time because housing value growth has outpaced income growth. But the flip side of this is that because housing values have grown so much long term, outstanding housing debt represented just 17.6 per cent of the asset value at the end of 2022.

“Debt levels are undoubtedly high, so it is important that Australian unemployment remains contained to support mortgage serviceability,” she continued, but noted that amid cash rate rises, outstanding mortgage rates in Australia have increased an average of just over 200 basis points (bps) for owner-occupier and investor loans.

“However, this could arguably be a positive for Australia. The fast transmission of monetary policy was reportedly one of the factors that empowered the RBA to pause the rate-hiking cycle in April, according to a recent address from Governor Lowe.

“Australian mortgage holders have so far dealt well with rising rates. CoreLogic data shows little indication of an increase in distressed properties hitting the market, as the flow of new listings volumes remains subdued nationally (trending -14.8 per cent lower than the five-year average). APRA lending data to December showed the portion of the mortgage market associated with late repayments was rising, but remains low, at around 1 per cent,” she added.

CoreLogic’s head of research also reflected on house price changes, outlining that while house prices will “likely cool more in markets like Australia relative to other countries where households are more sensitive to rate hikes, and housing prices rose substantially during the pandemic”, a sharp decline in home values has already occurred.

“National home values declined a record -9.1 per cent from their peak in April 2022, before recovering 0.6 per cent last month. While it may still be too early to call the bottom of the market, the steep price falls to date have seen limited increases in home loan defaults or forced sales,” she said.

In conclusion, Ms Owen said, “Ultimately, the IMF reporting is important. It highlights key vulnerabilities in housing markets that exacerbate the risk associated with a surge in unemployment. But for now, there is room for cautious optimism about the Australian housing market.

“Many households have accrued strong savings buffers through the low interest rate period, and labour markets remain extremely tight. Housing market conditions are turning a corner amid low stock levels, rising demand from overseas migration, and consumer sentiment shifting higher as we approach what may be the end of the rate tightening cycle,” Ms Owen concluded.